The Ins and Outs of Compression

Compression is extremely important in music and guitar playing today. Electric and acoustic guitars along with pretty much every other instrument can use compression both in a guitar pedal or as a post-production to bring their tone to the next level. It can be quite daunting to begin to understand how compression works and what is actually happening to your sound when using a compressor. But don’t fret, by the end of this, you will know exactly what is going on when a compressor is engaged!

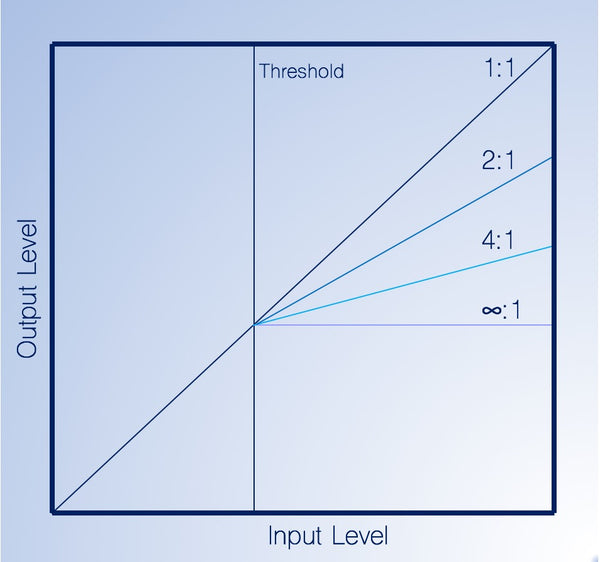

Essentially, the main goal of a compressor is to reduce the overall dynamic range of a signal (or sound). For example, a compressor can reduce a 12-decibel range (the distance between the loudest and the softest sound) down to 6-decibels or down to anything else, really. It does this by reducing (or compressing) signals that peak above a particular threshold. In other words, once the sound gets loud enough to reach the set level, the compressor is then activated and the level of the sound is turned down. Does this mean that if I play quiet enough and never reach the threshold, the compressor isn’t doing anything? Yes! Well, mostly. You see, some compressors can still color the sound of the guitar even when they aren’t necessarily “compressing.” This has to do with the electrical components inside the unit that might slightly alter the EQ of an input signal. But, this is a discussion for another blog post! For all intents and purposes, we can imagine that a compressor does nothing when the input signal fails to reach the threshold.

We now know that a compressor begins to work when the signal surpasses its threshold, but how do we know by how much the signal is reduced (or turned down)? That is where the compressor’s ratio comes into play. A compressor’s ratio determines how much the signal is turned down for every decibel the signal is above the threshold. For example, a common ratio is 3:1, meaning that for every 3 dB the signal is above the set threshold, the signal will be attenuated to 1dB above the threshold. Furthermore, with the same ratio, if a signal is 6 dB above the threshold, it will then be turned down to 2 dB above the threshold. With an 8:1 ratio, for every 8 dB over the threshold, the signal is set back down to 1dB over the threshold. With this pattern, we can see that there is more attenuation happening with higher ratios. For example, with a 4:1 ratio, when the signal is 8 dB above the threshold, it is brought back down to 2 dB above the threshold. This is a 6 dB reduction. However, with an 8:1 ratio, when the signal is also 8 dB over, it is brought down to 1 dB over the threshold, resulting in a 7 dB reduction.

Now that we are professionals with thresholds and ratios, let’s figure out how to cut our dynamic range in half. From my very first example, let’s say we had a dynamic range of 12 dB, ranging from 80 dB to 92 dB. If we were to reduce this range by half, our new range would be from 80 dB to 86 dB. This could be done a number of ways, but for this example let’s choose a 4:1 ratio and set our threshold to engage the compressor when the signal reaches 84 dB. This would work because when the input signal reaches its max value of 92 dB, the output will be 86 dB. Let’s think this through. 92 dB is 8 dB above our threshold of 84 dB. Thus, the input signal will be attenuated to 86 dB because for every 4 dB above the threshold, the signal is reduced to 1 dB above, and since this is 8 dB above, it is reduced to 2 dB above our threshold.

Notice that our original peak value is 92 dB (before compression) and our final peak value is 86 dB (after compression). But, when we use compressors we don’t want our output signal to be quieter than our input signal. This is why compressors have what is known as “make-up gain” to make up the volume that was lost. All we need to do is turn up our make-up gain 6 dB and we are golden. Our new range is 86 dB to 92 dB. We now have our output signal at the same level as our input signal with essentially the quiet parts in the signal louder. This is the heart of compression.

Ok, that got real mathy real fast. Crunching numbers all the time isn’t always the most practical way to use a compressor. I mean, when I play guitar I don’t use an SPL meter to do a bunch of comparisons between my input and output levels to make sure that I am reducing the dynamic range of my playing by a fourth or anything crazing like that. However, I do think of the overarching concepts of compression, and this helps me to set up my compressor efficiently for what I need it for. It also prevents me from misusing my compressor and killing my tone.

There are two more vital parts to a compressor that we should know about: the attack and release times. The attack time in a compressor will determine how long the compressor takes to reach our set compression ratio. For example, a common attack time for guitars is 25 milliseconds. This means that once the guitar is strummed, it will take 25 milliseconds for the compressor to gradually go from a 1:1 ratio (no compression) to the set ratio (3:1, 4:1, 8:1, etc.). A compressor’s release time does the opposite. It determines how long the compressor takes to go back to no compression. One thing to note is that the attack and release times in a compressor gradually switch from compression to no compression and vice versa. In other words, it’s not like there is a switch between no compression and compression, rather think of it as a ramping up and down of compression. The reason for this is to prevent compression from being too noticeable or abrupt.

If you made it this far, congrats! If you just skipped to the end to try to find shortcuts of how to use a compressor, well, fine I’ll give them to you.

Takeaways/advice

- Set your ratio before your threshold (determine how hard you want to compress before setting the level to activate compression)

- The higher the ratio, the harder the compression

- Attack and release times determine the ramp up and ramp down to and from our ratio

- Attack and release times should be set after the ratio and threshold have been set

- The make-up gain should be the last thing set on a compressor (try to match the level of the processed and bypassed signal by turning the effect on and off)

- Common guitar ratios: 2:1-4:1

- Common guitar attack times: 20-35 milliseconds

- Common guitar release times: 200 milliseconds